Maryland Is Bringing Back Oysters; Will Global Warming Ruin a Decade of Work?

77 oyster restoration areas in the Chesapeake Bay are threatened by abnormal sea surface temperatures, according to my analysis.

The first night I was in Baltimore for the National Institute for Computer-Assisted Reporting (NICAR), Krystal and I wandered into a local restaurant to try the crab cake and oysters. “Texas might have oysters from the Gulf of Mexico,” she said, “but East Coast oysters are meaty, sweet, and unlike anything you’ve ever tasted. Try them, and I promise you’ll never look at oysters the same way again.”

People often associate oysters with the city’s upscale raw bars or elaborate seafood towers, but oysters were once abundant throughout the Chesapeake Bay. In the 1880s, the Bay supplied nearly half of the world’s annual oyster demand, with scholars comparing the harvesting frenzy to the California Gold Rush.

Unfortunately, like the Gold Rush, this wealth was also fleeting. By the turn of the 20th century, natural oyster habitats had been greatly diminished thanks to overharvesting, pollution, and disease, and they have since continued to deplete. The native oyster population has dropped to a shocking 1% of its historical levels over the past decades in Maryland.

But losing oysters translates to more than just the rising prices of a delicacy on the dinner table. It also signifies a loss of a natural filter that is critical to the health of our seawater. According to Marine conservationists, each adult oyster can filter up to 50 gallons of water a day, and an oyster bed can reduce the force of waves on wetlands, which protects coastlines from erosion.

To counteract this decline, Maryland Department of Natural Resources (DNR) began building sanctuaries and seeding Chesapeake Bay with young oysters. Thanks to their efforts, the oysters are making a comeback.

Pushed Hard

MDNR has made two key efforts, one of which was expanding the restoration sanctuaries in 2010.

Sanctuaries permanently close oyster beds to harvesting except in specific aquaculture lease sites, allowing oysters to grow undisturbed. The goal of this preservation is to build a strong breeding population of oysters that will build the reefs which provide crucial habitats for other bay species.

In Maryland, the estimated population of native eastern oysters hit a historic low in 2004, dropping to just 19 tons. This figure represents only 0.21% of the historical peak since 1950, according to my analysis of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration(NOAA) Fisheries data.

Maryland introduced the Oyster Restoration and Aquaculture Development Plan in 2010, which expanded oyster sanctuaries to help rebuild the Chesapeake Bays native oyster population.

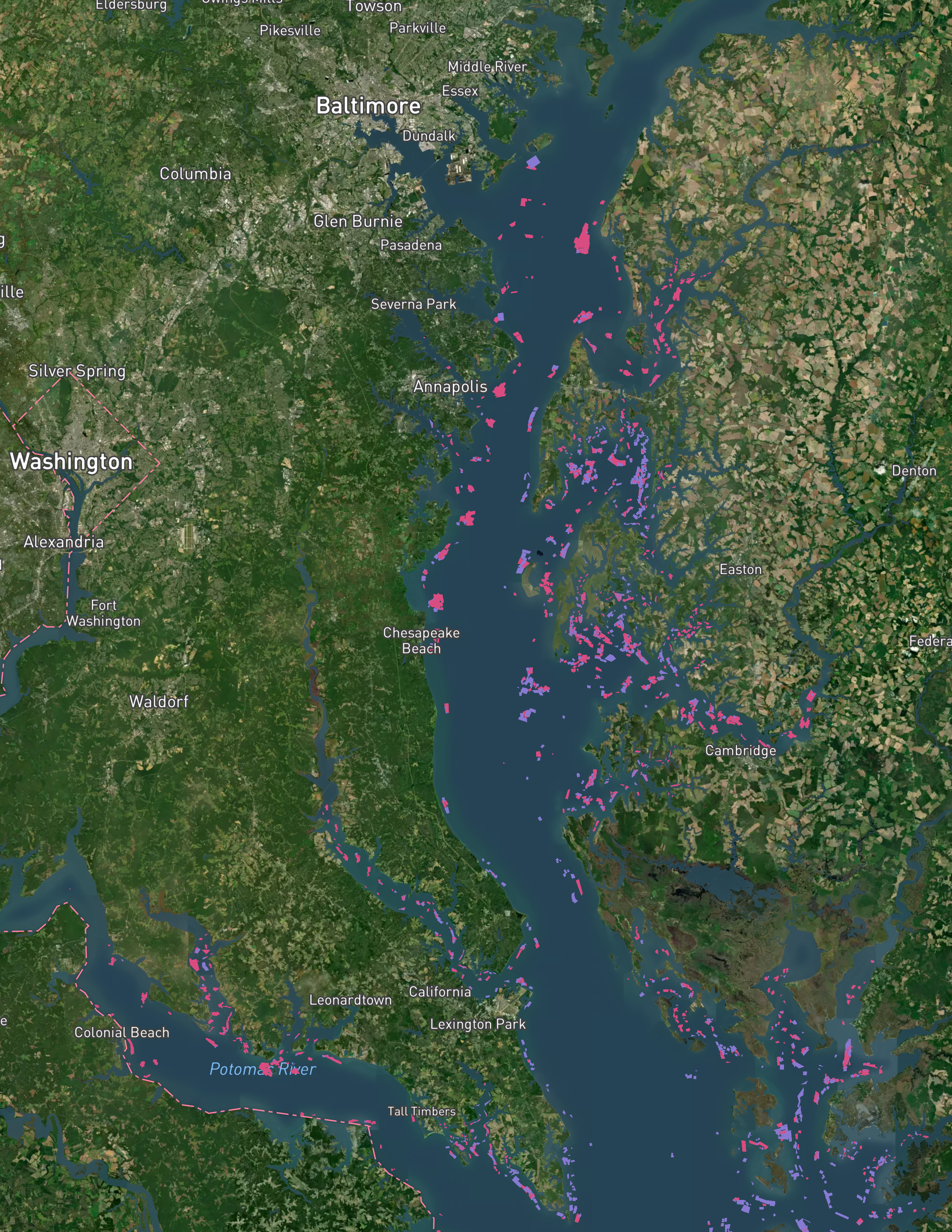

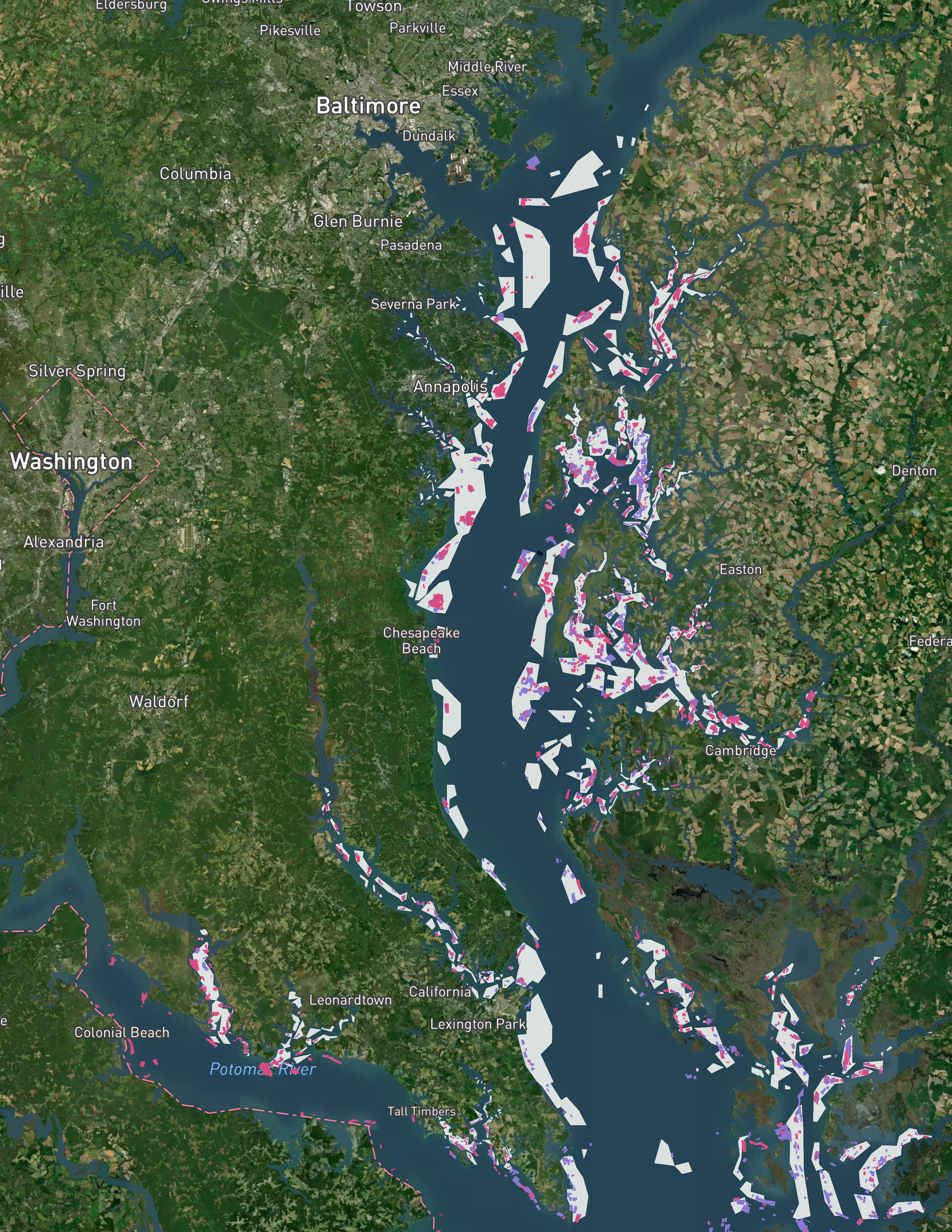

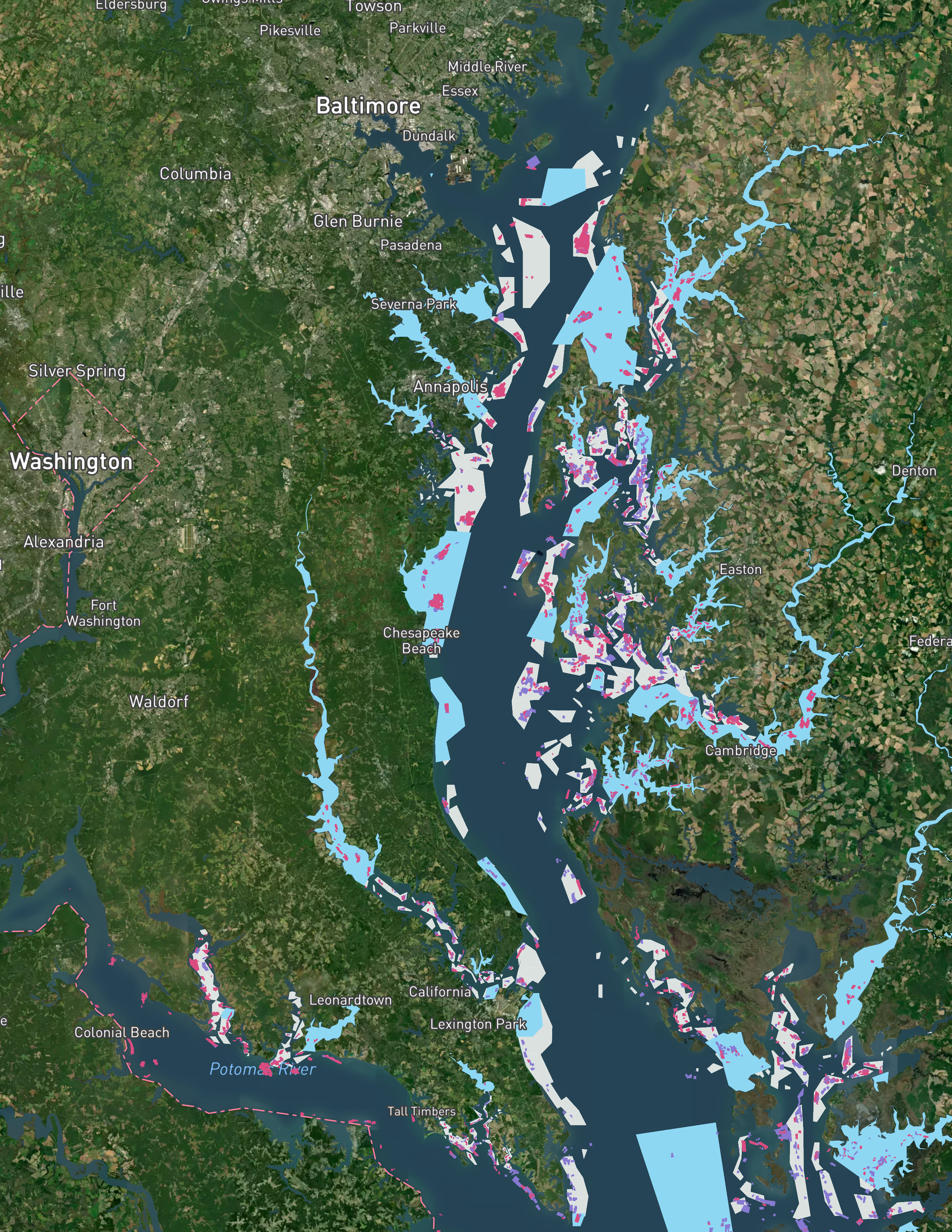

Under the new plan, as of 2022, the Maryland government designated and deployed an additional 844.24 square kilometers of oyster sanctuaries—a 369.09% increase compared to the area before 2010, based on my analysis of the sanctuaries map published by MDNR. (Scroll down to see the map.)

In 2014, Maryland partnered with NOAA and other nonprofit organization to launch the Oyster Restoration Plan. This initiative targeted 10 Chesapeake Bay tributaries and was committed to rebuilding oyster reefs by creating a substrate base and planting hatchery-produced juvenile oysters or seeding remnant reefs.

Data from MDNR shows that Maryland's oyster planting efforts date back to 1953. Various methods are used to restore oyster beds, including planting oyster seeds and placing shells.

This is the Chesapeake Bay.

The first method typically includes the addition of oyster seed, such as hatchery seed or wild seed planting to increase the likelihood of restoration success.

The second effort involves using substrate materials to build oyster reefs in the bay, ideally through fresh shell planting. Oyster crews and aquaculturists recycle oyster shells from business, but there aren’t enough to meet the state’s projected restoration needs. As a result, dredged shells, mixed shells, or alternative materials such as stones, concrete, porcelain, or steel slag are commonly used instead.

If the map for the second box is not activating, try scrolling down and then back up. You should see the map with only the pink and purple planting areas. Debugging...

Before 2010, Maryland primarily relied on wild seed planting, dredged shell addition, and limited fresh shell planting to repair oyster beds. However, since 2010, hatchery seed has become the dominant method.

Once abundant throughout Chesapeake Bay, oysters historically covered a total area of 215350 acres. New restoration areas overlap with 72.76% of historic oyster beds.

By 2010, 43% of the historic oyster bed area was legally protected and designated for restoration, increasing to 46% by 2022.

“We’re making significant progress,” the NOAA announced in a press release on their website . “Through the end of 2023, our team has planted 6.85 billion oyster seeds in Maryland as part of the effort.”

In the 2022-23 season, Maryland watermen harvested about 720,000 bushels of oysters from public fishing areas — the largest-recorded harvest since the late '80s. It marks the second record-high year for a wild harvest in Maryland.

Is Rising Sea Temperature a New Threat?

With native oyster populations nearly depleted, aquaculture has become a vital source for hatching more oysters to support the industry.

Winter is a critical season for those oyster hatcheries. During this time, adult shellfish are placed in warm, algae-rich water to induce spawning. Hatcheries collect the eggs, then hatch and grow the oysters, which are then sold to farmers for further cultivation.

But warmer winters are not favorable for wild oysters. The slowly increasing temperatures are creating new challenges for restoration efforts in nature.

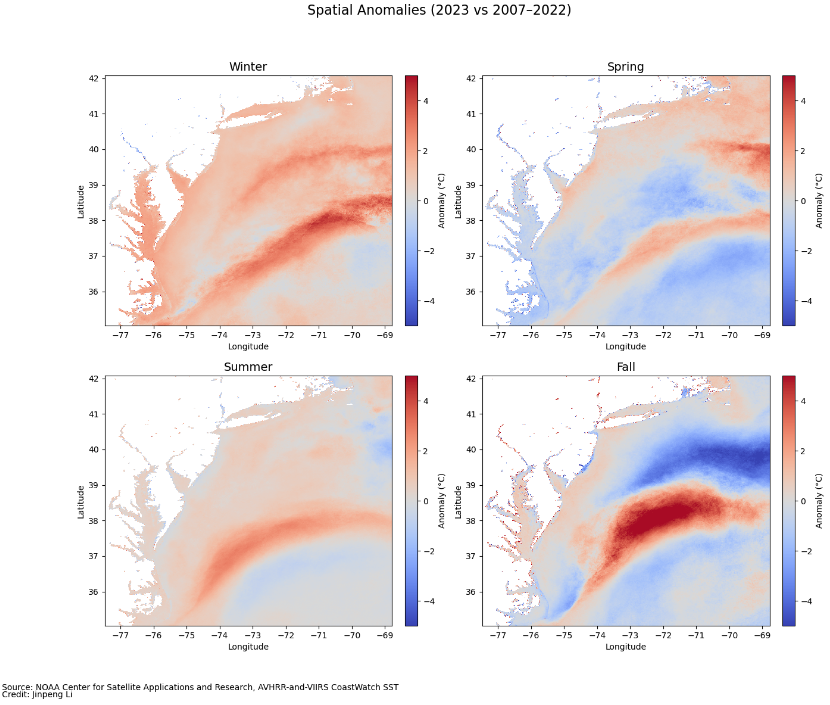

The Chesapeake Bay in particular is experiencing a worrisome trend in rising temperatures. In 2023, the average sea surface temperature increased by 1.09°C in summer and 0.43°C in winter compared to the 2007–2022 average. While fluctuations of up to 2°C are within the normal range, these numbers only represent the average.

When comparing restoration areas with sea surface anomalies, my analysis of NOAA satellite data found that 71 sanctuary areas experienced abnormal winter temperatures exceeding 2°C. Most of these sites cluster near Southern Maryland—as if they’ve got front-row seats to the quirks of Maryland's warming waters.

Rising sea temperatures disrupt oysters' natural cycles, potentially causing premature or delayed spawning and reducing their reproductive success.

(To Be Continued...)